The cost of escalating sanctions on Russia over Ukraine and Crimea

– sanctions are not about how much damage can be inflicted on the sanctioned, but how much pain the sanctioner can tolerate

by Georg Zachmann on 18th March 2014

The United States and the European Union responded to Sunday’s Crimea referendum – which overwhelmingly backed union with Russia – by imposing sanctions on Russia. So far, 21 Russian and Ukrainian officials, allegedly responsible for the sovereignty transgressions, have been slapped with asset freezes and travel bans. EU leaders will meet again on March 20-21 to discuss possible additional sanctions.

Sanctions and retaliation are obviously a negative sum game. If countries stop their cooperation in certain areas, both sides lose. Sanctions are part of a political game of escalation in which both sides signal how much value they put on an issue. The west seems to have a better hand (sanctions hurt Russia more than they hurt the west) but Russia seems to put a higher value on union with Crimea, so the outcome is unclear.

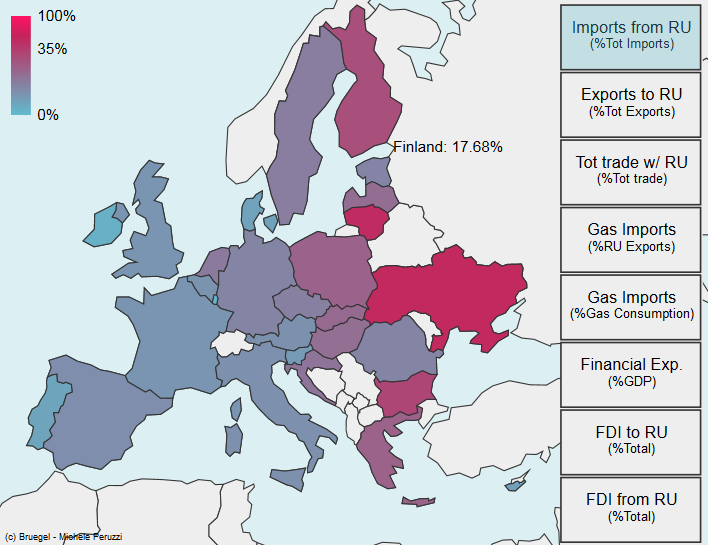

Furthermore, the heterogeneity of EU member states‘ interests (see below) raises doubts within the Kremlin about how determined the EU will actually be. It is precisely because of this ambiguity of positions that the escalation game is being played – if the outcome was clear, everybody would be better off by not playing this game.

What further sanctions?

The type, timing and size of sanctions is a political calculation. Both sides want to convince the other that they are willing to go furthest. Sanctions could range from targeted and time-limited visa bans for certain persons up to full-blown economic sanctions against the entire country.

The direct cost of sanctions is often less important than the losses in terms of mutual trust. For example, the economic cost of not delivering/purchasing an agreed amount of natural gas can be limited, given that storage can buffer the impact of such a trade disruption. But exploiting the vulnerability of a trade partner can cause mistrust that might persist long beyond the end of the actual conflict.

Sanctions against certain ‘influential’ oligarchs might have the side-effect of weakening political support for the Kremlin’s policy. But one might equally argue that this would not work because the security of the oligarchs’ assets (and maybe more, as Mikhail Khodorkovsky found out) seems to depend on the good-will of Putin, not vice-versa. In fact, it is much more likely that targeted Russian sanctions against EU member states with a less pronounced interest in the political issues at stake (eg Germany) might undermine European political unity.

Different impact in different member states

A single country (Russia in this case) might find it easier than a group of countries with very different preferences to devise a ‘convincing’ strategy. The economic and political cost and the political benefits of sanctions are very unevenly distributed between European member states, and will depend on the type of sanctions.

Sanctions targeting Russian financial assets might have a substantial impact in southern Europe (see an extensive discussion in Silvia’s blogpost on Russian roulette). The distribution of the impact of trade sanctions can be approximated by Russia’s share of the foreign trade of different member states. The cost seems to mainly fall onto the countries of the eastern belt of the EU, from Finland to Greece, with the notable exception of Romania, which is less affected. In relative terms, Germany would not be more affected than the Netherlands or Sweden. Sanctions targeting only Russian gas imports would have a much more substantial effect on the same group of countries. In addition, the central-west European countries Germany, Italy, France and the Netherlands would be affected by this. Finally, in terms of financial exposure (in the map: consolidated foreign claims on ultimate risk basis relative to GDP), Austria sticks out. The distribution of the cost of sanctions depends on the type of sanction chosen.

This is bad news for building a persuasive European negotiating position, because when it comes to distribution of cost, Europe often prefers a lowest common denominator approach.

What should Europe do?

Before any decision on sanctions is taken, Europe should clarify what it wants to achieve with sanctions. Possible political goals are to reverse Russia’s de-facto annexation of Crimea, to prevent Russia from going beyond Crimea or to just save face.

Then, the leaders of the European Union should understand how far each of them would be willing to go. If the member states cannot commit to the level of sanction-induced costs that would have a realistic chance of changing Putin’s mind, Europe will have to restrict itself to symbolic measures to avoid unnecessary losses.

If the EU is willing to accept the increasing costs of the escalation, the first step should be to give a convincing signal of unity and determination – otherwise it will be seen as an invitation to test Europe’s strength. Taking incremental steps might take too long, and would make the big steps look small. If escalation is spread over a long period of time, it might also on aggregate inflict more economic damage, and on-going rhetoric might reduce the political room for both sides to come back to the table. By contrast, a determined step could shorten the escalation period and could allow normal cooperation to be resumed quickly after the crisis.

Sanctions are not about showing the other how much damage can be inflicted on the sanctioned party, but about demonstrating how much pain can be tolerated by the sanctioner. If the EU wants to go all-out over Crimea, stopping gas imports from Russia would be a powerful signal with limited long-term consequences (a similar proposal has been made by David Böcking).

Europe might not be able to fully replace the 130 billion cubic metres it imported in 2013 at sufficiently low cost. But the Russian economy would be severely hit. At an average sale price of US$350 per thousand cubic metres, the annual loss in Russian revenues would be in the order of US$70 billion or three percent of GDP.

With this step, Europe would defuse Russia’s gas weapon at a stroke. Most importantly, when normal economic relations are re-established, the long-term impact of this episode would be minor. Russia will remain an important source of gas for Europe, simply because it is so uneconomic for Russia to diversify its gas exports.

Finally, it is much more powerful for Europe to stop imports, compared to a scenario in which Russia stops exports of natural gas. Stopping gas imports is an expensive signal – but a high price is the precondition for demonstrating determination. Such a bold strategy could obviously only work if energy solidarity inside the EU is ensured.

Research assistance by Michele Peruzzi and Carlos de Sousa is gratefully acknowledged.

Map sources.

Imports, Exports and Trade data: IMF. 2012 data. Gas Imports (Imports from Gazprom) and Russian Gas Export data: Gazprom, Sberbank Investment Research 2014. 2012 data Gas Consumption: Eurostat. 2012 data Financial Exposure (Consolidated foreign claims on ultimate risk basis) over nominal GDP: BIS table 9D and IMF. Outstanding amounts as of September 2013, except for Austria (September 2012). Foreign Direct Investment: IMF. 2012 data.